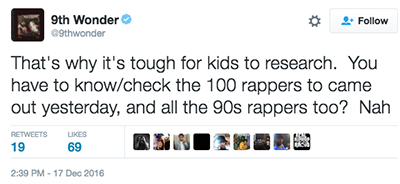

As the number of new hip hop artists has grown drastically in the past decade, resulting in the explosion of new hip hop releases, the opinion that millennials face an overwhelming prospect in trying to study the hip hop canon while keeping abreast of the latest hip hop music has continuously gained footing in recent years. This past Sunday (Dec. 18, 2016), 9th Wonder, one of the Post-Pioneers Era’s[1] most respected and accomplished producers, posted the following on Twitter:

“That’s why it’s tough for kids to research. You have to know/check the 100 rappers to came out yesterday, and all the 90s rappers too? Nah.”

Researching hip hop’s music history while keeping up with hip hop’s present number of new music releases may seem to be a difficult task, but this view overlooks several key things: (1) What music canons are really about, how and why they come to be, and how they actually help streamline the flow of research for emerging artists; (2) That hip hop recording artists, old and new, have always researched the music that they’ve felt they needed to in order to develop; and (3) That the technology that exists in this era to help with such research is phenomenal.

Canons of Works in Music

In music, just as with literature, a canon of work refers to a collection of songs, albums, and artists that represent well-recognized standards and best practices (creatively speaking especially) within a specific genre, music tradition, or form. For example, the canon of soul music includes songs like “Say It Loud — I’m Black and I’m Proud,” “We The People Who Are Darker Than Blue,” “Day Dreaming,” “Don’t You Worry ‘Bout a Thing,” “To Be Young, Gifted, and Black,” and “What’s Going On.” And this canon is populated with artists like James Brown, Curtis Mayfield, Aretha Franklin, Stevie Wonder, Donny Hathaway, Marvin Gaye, and many more.

Music works, and the artists who make them, achieve canonical status once they are widely recognized as solid examples of a specific music tradition. Although a canon necessarily exists in perpetuity, it can not grow retroactively, only chronologically. This is to say that the canon of ‘60s or ‘70s soul music can not be expanded by someone today singing perfectly within the borders of those same traditions. However, someone today who is influenced by ‘60s and ‘70s soul music can, drawing upon those influences, add to what will become this era’s canon of soul music. And this era’s canon is then added somewhere to the larger soul music canon.

This works the same way in hip hop/rap music. The canon of ‘80s and ‘90s hip hop includes songs like “Sucker MC’s,” “Road to Riches,” “Ain’t No Half Steppin’,” “The Symphony,” “Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos,”“Mass Appeal,” “Around the Way Girl, “Nothing But a G Thang,” “Memory Lane (Sitin’ in da Park),” “Passin’ Me By,” “Who Got the Props,” “Juicy,” “Feelin’ It,” “Dear Mama,” “My Philosophy,” “Looking At The Front Door,” “Straight Outta Compton,” “I Got To Have It,” “Broken English,”“Shook Ones, Pt. II,” “Check the Rhime,” “Get At Me Dog,” and “Rosa Parks.” And this canon includes artists and beatmakers (producers) like Run-DMC, Marley Marl, LL Cool J, NWA, Rakim, Kool G Rap, Big Daddy Kane, Gang Starr, Rick Rubin, KRS-One, Jay Z, DJ Premier, Nas, Dr. Dre, Notorious B.I.G., Pete Rock, Outkast, A Tribe Called Quest, RZA, J Dilla, Ed O.G. and Da Bulldogs, Boogie Down Productions, Main Source (Large Professor), Common, The Pharcyde, Just Blaze, Public Enemy, and many more.

The canons of ‘80s or ‘90s hip hop music can not be expanded by someone today even if they’re rapping or producing perfectly within the borders of those traditions. Still, someone today who is influenced by the ‘80s or ‘90s can, utilizing the aesthetics, compositional designs, tropes, etc. specific to those eras, create music that can be added to post-2000 era’s canon.

So it should be understood that new music canons — which exist in the broader canon of a specific music tradition, form, and genre — are always an amalgamation of what came before and what currently exists. Whether the balance skews in one direction (the past or the present) for an emerging musician does not diminish the fact that new music (like all art) fundamentally requires research of both the past and the present. In other words, the task of researching canonical hip hop/rap is not, and can not ever be, the culprit, primarily because the canon, serving as the standard, actually caps the amount of music that one needs to research, but also because present-day tools for accessing hip hop’s/rap’s canon are exceptional.

You Grow Up in the World You Know, Not the One You Don’t; and Music Has Always Been Proportional to the People Making It and the Channels of Distribution

We come to age in the world that we know, not the one that we don’t know. In terms of culture and, more specifically, access to culture, every generation has its own tools of access, i.e. mechanisms and systems by which it can access art and culture like hip hop/rap music. Broadly speaking, for music these mechanisms and systems include things like radio stations, music television shows, and, most importantly, audio devices. Each of these access channels help individuals of a given generation to access and disseminate the flow of old and new music.

Put simply, the level of music output has always been directly related to the number and types of ways that music can been discovered and researched.

As a matter of course, when technology advances, the tools of production become democratized, literally and figuratively. This allows for (and often prompts) an increased number of new products on the market. In terms of music, this means that as more people have access to cheaper, more powerful technology, the number of new recording artists increases, and naturally the number of new music releases spike as well. This is inevitable. But this also means that, while technology allows for more artists and more music, it also provides more channels — new shows or new technology like streaming — to help people access the uptick in the increased flow of new artists and releases.

Millennial Listening Habits Are Actually Conducive to Extended Music Research

The people of any given generation always view the output of music in their time as the norm (the world they know), and they adjust their listening activities accordingly. Take for instance my son’s flight from Paris to New York earlier this year. Sitting on the flight, he told me nonchalantly, that he had listened to Solange’s album A Seat At the Table, Little Simz’s album Stillness in Wonderland, Capon N’ Noreaga’s debut album, The War Report, Ohio Players’s Ecstacy album, and two albums by The Intruders, Cowboys to Girls and Save the Children — all in the span of a seven-hour flight. This type of listening activity is normal for him and his generation (long flight or not), mostly because he has grown up in a time where technology makes it possible for him to seamlessly bounce back and forth between different music eras and artists with portable devices at any given moment.

If you grew up with four “channels,” e.g. a few radio stations, one music video television channel, several music magazines, that was your norm. So ten channels, for instance, might seem to you to be too many channels. But what if you grew up (or are currently growing up) with ten or even one hundred channels? If one hundred channels is your norm, you adapt and self-curate, just as generations have done before.

The idea that all people from any given generation have always listened to the same music at the same time is a myth. What is more accurate, and what leads to a different debate altogether, is that the fewer the number of channels, the more likely it is people are listening to more of the same music, more of the time. Increase the number of artists and the number of new releases, inevitably, the number of channels increase as well… This means people are listening to a broader selection of music at different times. Thus, this is an issue of access and how music is curated, not an issue of too much research for later generations to research.

The point I hope to make here is that millennial listening habits are naturally different than generations prior primarily because millennials have access to more music and more channels by which to consume it, for instance, music streaming services that put the entire audio catalog of the world at your fingertips. Therefore, millennials are actually better wired and equipped to do the sort of hip hop/rap canon research that some say is a tough haul.

When most people think of Wiz Khalifa, do they think of early Wiz? The Wiz on the “Show and Prove” intro, or “Stay In Ur Lane,” a song’s whose first verse includes Wiz rhyming: “I’m too hot/ mix Jay, Big, and 2 Pacs”? OR, do they think of the Wiz Khalifa known for “We Dem Boyz?” Wiz’s talent is the direct product of researching hip hop’s/rap’s canon while maintaining the pulse of his own generation’s music trends and developments.

Hip Hop’s Canon of Music is Very Accessible

In my book The BeatTips Manual (subscribers can download it for free), I spotlight fifteen noteworthy hip hop/rap albums between 1988 and 1994 that personify the bedrock developments of the art of beatmaking. This is not to so say that there were no new developments in beatmaking after 1994; indeed there were and in my book I cover every major beatmaking development through 2016. The point is that this spotlight of fifteen albums, which serves as a research pathway, is also essentially a playlist. Playlists represent one of the chief means by which all generations, not just millennials, consume music today. But for millennials, those who have grown up with playlists, such systems serve as one of the primary aids by which they actually do music research, not simply casual listening.

When you point a millennial in the direction of a song or album from the canon of hip hop, they have shown a remarkable knack for going down the proverbial rabbit hole and engaging in the sort of deep-dive research that permits one to gain a more comprehensive understanding of a by-gone era. And millennials do this not necessarily because their taste in music leads them there, but more often than not because they have better (technological) systems at their disposal.

Millennials are actually wired to do the exact kind of deep-dive music research that other musicians have had to do in order to create and innovate their way into any given music canon. Thus, giving credence to the notion that there’s simply too much past hip hop/rap music (or any genre for that matter) for millennials to uncover, research, and learn about is actually a counterproductive message. This message, which also indirectly places a veil of secrecy over important hip hop/rap history and enshrines the past, especially the ‘90s, as the supreme era of hip hop/rap, gives millennials an excuse for not researching hip hop’s/rap’s canon. But this is a pass that millennials, like generations before them, neither asked for or need.

The point I hope to make here is that millennial listening habits are naturally different than generations prior primarily because millennials have access to more music and more channels by which to consume it, for instance, music streaming services that put the entire audio catalog of the world at your fingertips. Therefore, millennials are actually better wired and equipped to do the sort of hip hop/rap canon research that some say is a tough haul.

How Else Do We Explain Millennials Who Are Fluid in Past and Present Aesthetics? Five Millennial Artists Where Research of the Canon is Obvious: Kendrick Lamar, Joey Bada$$, Wiz Khalifa, Mac Miller, and King Bliss

Kendrick Lamar is revered as a voice — some might argue the voice — of this present hip hop/rap generation. His relevancy is based upon his head-on approach to topical themes just as much it is to his master-level rhyme skills and knack for picking instrumentals. Unquestionably, this is because Kendrick Lamar is a student of hip hop’s/rap’s canon and a product of his own generation. His music, which itself will undoubtedly one day serve as a tent pole in hip hop’s/rap’s canon, much like LL Cool J, Kool G Rap, Rakim, Pac, B.I.G, Jay Z, Nas, Ghostface Killah, and others, is embodied with the standards and aesthetics of the hip hop/rap canon.

The Kendrick Lamar who made noise in 2005 with his mixtape Hub City Threat — which includes “Compton Life,” a song where Jay Z’s influence (as well as other pre-2000 tropes) is quite apparent — and the Kendrick Lamar who dominated 2015 with his instant classic How To Pimp a Butterfly draws from two wells: Hip hop’s/rap’s canon and the trends of his generation.

When most people think of Wiz Khalifa, do they think of early Wiz? The Wiz on the “Show and Prove” intro, or “Stay In Ur Lane,” a song’s whose first verse includes Wiz rhyming: “I’m too hot/ mix Jay, Big, and 2 Pacs”? OR, do they think of the Wiz Khalifa known for “We Dem Boyz?” Wiz’s talent is the direct product of researching hip hop’s/rap’s canon while maintaining the pulse of his own generation’s music trends and developments.

No one could say that Joey Bada$$’s “Teach Me” feat. Kieza was not a so-called dance song. And some might say that the song was part of his concerted effort to crossover to a broader audience. Either way, the song was a hit because Joey Bada$$ executed the style and sound that he was going after, a style and sound familiar to this era. But what about Joey Bada$$’s earlier work, specifically the DJ Premier produced “Unorthodox?” How could Joey Bada$$ so convincingly pull off the style and sound of the ‘90s if he did not study it prior? It stands to reason that he was able to rhyme (so convincingly) in a style and sound reminiscent to the ‘90s — over a post-‘90s DJ Premier beat no less — precisely because he researched the ’90s chamber of hip hop’s/rap’s canon.

What about Mac Miller? His earliest acclaim included “Kool Aid & Frozen Pizza,” a song who’s instrumental doesn’t just summon up the essence of ‘90s hip hop, it directly borrows it in the form of a sample of Lord Finesse’s beat for “Hip 2 Da Game.” Jump forward to 2016 and Miller had bolstered his presence with an album that touted happy dance numbers like “Dang” (feat. Anderson .Paak); but Mac Miller was still capable of pulling off classic sample-based odes like “Brand Name” (2015).

Finally, there’s King Bliss, a rapper from Canada who’s debut single “Money Mantra” BeatTips featured. On “Money Mantra,” King Bliss’s style and sound is quite similar to that so-called ‘90s essence, yet he also sounds fresh and in the now, this despite the fact that “Money Mantra” employed a ‘90s-style sample-based beat and not a post-2010 trap-based instrumental. Again, how do we explain King Bliss’s fluidity in a style and sound twenty years older than he is? And how do we explain his ability to still sound like what’s happening now?

King Bliss is not as known as Kendrick Lamar, Wiz Khalifa, Joey Bada$$, or Mac Miller; he’s at the beginning of his career, as were Kendrick, Wiz, Joey, and Mac years ago. Still, I mention all five of these rappers (and no doubt there are more) in concert because they all made the deliberate decision to, on some serious level, research hip hop’s/rap’s canon and use it to help fuel their own unique style and sound. Are each of these artists exceptions, random outliers who simply had the stamina to take on the task of researching the canon of hip hop/rap? Or did they (do they) all aspire to not simply be recognized by their peers in their own era, but to also be added to hip hop’s/rap/s canon one day? Further, am I on safe ground when I say that like Kendrick, Wiz, Joey, Mac, and King Bliss, there are countless millennials who see researching hip hop’s/rap’s canon — along with keeping abreast of the latest trends in hip hop music — as the path to their own unique development?

The truth about this era is that mediocrity, the bare minimum, and unashamed style-jacking is enough to make you a standout. Put another way, in today’s era, you don’t need to study hip hop’s/rap’s canon to establish a platform; merely copying what came out last week (sometimes literally) is all you need to do. But this isn’t a path that millennials are obligated to take. And this certainly doesn’t mean that a phantom “skip hip hop/rap research” pass should be conflated with the widespread acceptance of mediocrity. If a millennial chooses to skip out on studying hip hop’s/rap’s canon, then call that a personal choice borne from that specific millennial’s individual aspirations. But let’s not excuse such skipping by all millennial’s as the by-product of there being too much hip hop/rap to study. If anything, those of us who are knowledgeable of the hip hop/rap canon should be clear about what abandoning the hip hop/rap canon could mean just as much as we express the benefits of researching it.

As every serious artist in or scholar of hip hop/rap will tell you, you never stop being a student of the culture and the music. So there can never be too much to learn because you can’t possibly learn it all. But you can learn what it takes to one day earn your own in place in hip hop’s/rap’s canon. And frankly, that’s the tough part.

[1] In my book The BeatTips Manual, I describe the eight distinct (major developmental) periods of beatamking, including the Post-Pioneers/Avant Garde Period. Paid subscribers can download The BeatTips Manual for free.

The music and videos below are presented here for the purpose of scholarship.

Kendrick Lamar – “Compton Life”

Kendrick Lamar – “Alright”

Wiz Khalifa – “Show and Prove Intro”

Wiz Khalifa – “We Dem Boyz”

Joey Bada$$ – “Unorthodox”

Joey Bada$$ – “Teach Me” feat. Kiesza

Mac Miller – “Kool Aid And Frozen Pizza”

Lord Finesse – “Hip 2 Da Game”

Mac Miller – “Dang” feat. Anderson .Paak

Mac Miller – “Brand Name”

King Bliss – “Money Mantra”

Yes, millennials need to abandon hip hop/rap! They need to get re hooked on oldies. 70s, 80s, 90s, R&B, Old School, and slow songs! Not that horrible vulgar music that is nothing but profanity, yelling, glorification of the gangster life, and is listened to by thugs, killers, gang bangers, and even terrorists.