The Single Most Important Thing About Rhyme and the Significance of the Core Rhythm and Groove

If you’re bold enough to set out on that journey of writing rhymes, then it’s damn well something you better have. But how do you get it? When it comes to rhyme, the typical thing to do is study the rhyme-greats of the hip hop/rap tradition.

For those fairly new to rapping (and here, I’m talking 5 years experience or less), the easy starting point is Jay-Z, Biggie, Nas, Eminem, Kanye West, you get the picture. And for those willing to take it back—that is, those interested on discovering the core metrics of the modern lyrical skill set, there’s the mighty lyrical sextet of T La Rock, Silver Fox, LL Cool J, Rakim, Kool G. Rap, and Big Daddy Kane. (NOTE: there are some who focus on the trinity of Rakim, Kool G. Rap, and Big Daddy Kane to the exclusion of LL Cool J. I can assure you that such an act is utterly, ridiculously, stupendously, and but-ass-crazily foolish, as early LL Cool J is lyrical sickness! That’s “dope” for all the squares who front, or “amazing” for the part-time rap reviewers and crowd followers.)

For the extra accelerated students of rhyme, you know, those who want to know the base components of the rap tradition, the origins of it all, there’s the “originator’s class”—Melle Mel, Grandmaster Caz, and Kool Moe Dee, and the countless unsung M.C.s from 1973-1978. Anyone of the aforementioned dimensions of hip hop’s rhyme lexicon that I’ve laid out here will give you some level of skill. But if you want to really teleport to the essence of the oral tradition of “rap” that gave way to modern “Rap”, then you have to go off the path—way off the path…

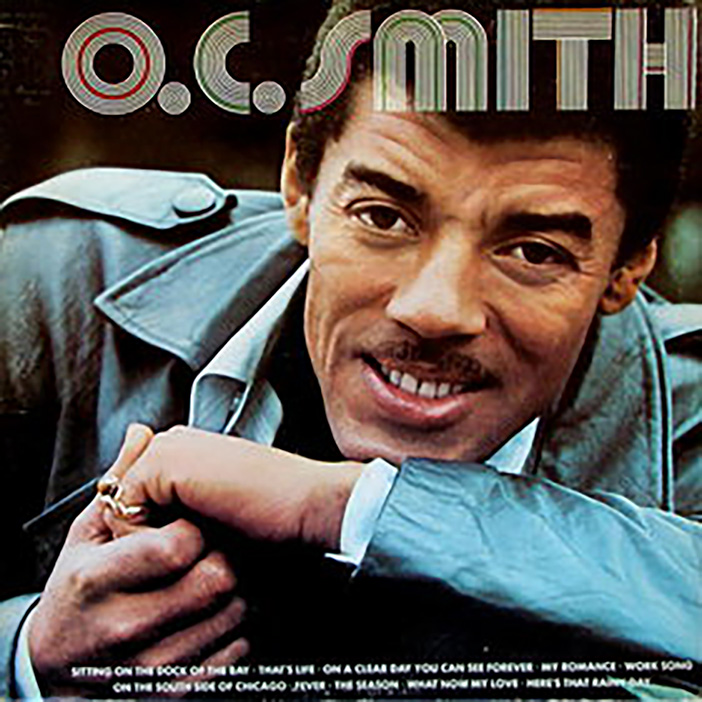

This is where I found myself years ago, fever-thinking about how to improve my rhyme skill. Regular BeatTips readers know that I began rapping before I made beats. And for me, the goal was to capture skill and develop my own unique voice. This meant that not only did I have to study the greats of hip hop’s rhyme lexicon, I had to find a horizon that not too many rhymers had gone to before. And I found that horizon in O.C. Smith’s “Blowin’ Your Mind” from the Shaft’s Big Score soundtrack (1973).

Modern rhyme lexicon aside, nothing taught me more about how to rhyme than O.C. Smith’s rap (lyrics by Gordon Parks) on “Blowin’ Your Mind.” Smith, an acclaimed vocalist with a background in jazz, does more high-level rapping than singing on “Blowin’ Your Mind.” First, there’s the natural adlib before he begins the first verse. After the instrumental has cooked, twisted, turned, and rattled for 1 minute and 24 seconds, and after the horn section does a 4-second staccato crescendo, Smith slides in abruptly-smooth with the command, “Now, look here…,” before he begins a rhyme that doesn’t focuses on rhyme itself:

Modern rhyme lexicon aside, nothing taught me more about how to rhyme than O.C. Smith’s rap (lyrics by Gordon Parks) on “Blowin’ Your Mind.” Smith, an acclaimed vocalist with a background in jazz, does more high-level rapping than singing on “Blowin’ Your Mind.” First, there’s the natural adlib before he begins the first verse. After the instrumental has cooked, twisted, turned, and rattled for 1 minute and 24 seconds, and after the horn section does a 4-second staccato crescendo, Smith slides in abruptly-smooth with the command, “Now, look here…,” before he begins a rhyme that doesn’t focuses on rhyme itself:

“Who twists your spine, till it feels like jelly and it heat your blood till it’s boiling wine?—/

Who splits your heart in a zillion pieces?—”

The magnificent thing about this two-line opening is that Smith doesn’t rhyme “rhyme”, he rhymes “rhythm”. That is, his lyrics go against and to the rhythm of the instrumental. Smith is not concerned with crafting a concise rhyme, he’s only concerned with putting you on to (or reminding you) just who Shaft is—a bad motherfucker! And for that purpose, the purpose of conveying in-your-face information in a heavily rhythmic lyrical cycle, Smith doesn’t even bother with a typical ABACDA rhyme scheme. Instead, in the opening verse, he runs off a deceptive AB-based rhyme scheme, where nothing “rhymes” cleanly or neat. He pulls this off with various oral techniques—vocal drags, gaps, pauses, and elongations, all of which he uses in deference to rhythm, with no emphasis on presenting a clean rhyme. It’s not until the third verse does Smith offer a clean AABBCCDD rhyme scheme:

“Wo, he’s a smooth cat/

And knows where it’s at/

A bad spade/

Don’t pull your blade/

A super brother/

A gone mother/

A cool dude/

And shovels his food—”

And even though this is the cleanest rhyme of the song, Smith’s delivery is anything but. He raps this rhyme scheme in a rhythmic breakdown, one that drives the instrumental bridge in the song. Skill.

It was upon listening to “Blowin’ Your Mind” that I made my most important discovery about the art of rhyme: Rhyming is about the rhythm of words and their relationship to the rhythm of the instrumental; that words rhyme cleanly, or even at all, is a secondary notion. This single thought, that rhyming, particularly at its highest level, is about the negotiation of two rhythms—that which the rapper brings and that of the instrumental—and words that mean what they say, gave me the basis for the rhyme skill I always sought. Not only did it give me a deeper understanding of how to master the various tropes and nuances of modern rhyme (1985-to the present), it helped me figure out everything from how to develop my own breath control techniques to how to identify those word frameworks that work best with my style and voice.

It was upon listening to “Blowin’ Your Mind” that I made my most important discovery about the art of rhyme: Rhyming is about the rhythm of words and their relationship to the rhythm of the instrumental; that words rhyme cleanly, or even at all, is a secondary notion. This single thought, that rhyming, particularly at its highest level, is about the negotiation of two rhythms—that which the rapper brings and that of the instrumental—and words that mean what they say, gave me the basis for the rhyme skill I always sought. Not only did it give me a deeper understanding of how to master the various tropes and nuances of modern rhyme (1985-to the present), it helped me figure out everything from how to develop my own breath control techniques to how to identify those word frameworks that work best with my style and voice.

But “Blowin’ Your Mind” didn’t just teach me more about rhyming, it taught me a great deal about how to make beats. When you first hear “Blowin’ Your Mind,” you’re struck by the cinematic orchestration of it all; of course, it was a theme song for a movie soundtrack, so that’s to be expected. But it’s the nature of this orchestration that interested me the most.

Everything centers around the rhythm and the groove. The bass part, deadly repetitive and menacing, stabs over and over with a 4-note sequence that splits anchoring duties with the drums. Then there’s the rattling tambourine and spots of the shaker here and there. And no Shaft-like instrumental would be complete (or perfect) without twanging rhythm guitar passes. The drums bump and role, certainly, but the earlier described bass sequence leads the rhythm section for the most part, so the drums are grounded, content with holding a steady backbeat. And sure, there’s a big, over-the-top brass section on “Blowin’ Your Mind,” but that was par for the course when it came to 1970s film scores. Only, the brass section here, just as with the strings, dances and jabs in and out to the movement of the core rhythm.

The main takeaway from my study of Gordon Parks’ arrangement on “Blowin’ Your Mind” was how to keep the core rhythm going, while adding in changes that didn’t corrupt the feel and mood. The type of beats that I’m mostly interested in (those that motivate me to wanna rhyme the most) are those that commit to a deliberate rhythm. I can appreciation orchestral beat productions (when they’re done right), but sometimes those beats come off as an overreach with useless changes and unnecessary sounds. Instead, I dig a well-maintained groove, one complete with a solid back beat and strong rhythmic force, where the melody defers to it. This is exactly what “Blowin’ Your Mind” offers. Skill.

Oh, yeah, my infamous “Gun-shot” snare drum sound was created from, and patterned off of, the snare at the :36 mark…

The music below is presented here for the purpose of scholarship.

O.C. Smith and Gordon Parks – “Blowin’ Your Mind”