Reward for Mediocrity Means that Rap Will Never Go Back to its Golden Eras, Where Vanguard Art Growth was the Norm

By AMIR SAID (SA’ID)

The norm in hip hop/rap music has changed. Success, both in the mainstream and underground, used to dictate that music makers strive for some modicum of excellence and originality. But now there’s a new norm: the idea that mediocrity is not just acceptable, it’s worth pursuing.

“Success” is just as good a subjective word as any other when talking music. How one defines success goes a long way in shaping their thoughts and actions. But if by success we generally mean three main things: notoriety, respect, and financial compensation, then success is still a constant. Fortunately, where skills-based beatmakers and rappers are concerned, having skills and craft integrity is still a constant. But for number of other beatmakers and rappers, the notion of skills, higher standards, and craft integrity has dissolved, and for valid reason.

Entry Point and Master Level: What Trap Music and the East Coast Sample-Based Styles and Sounds Can Show Us About the Safeness of Mediocrity

Trap music has a low entry threshold. As a beatmaking style and sound, its barrier to new beatmakers is quite low; as a rhyme style, its barrier to new rappers is equally low. In both cases, one can seemingly begin immediately without any skill, little knowledge of the art of beatmaking, or experience. Further, in this scenario, one can almost instantly make the sort of trap music that’s passable for much of what has already been accepted as decent. This isn’t a knock against trap music; it’s the reality of trap music’s range. Just as with any beatmaking or rhyme style, there’s a range to the style and sound. Thus, trap music has its entry point and its master level. For instance, making trap music on the level of DJ Toomp and T.I. is certainly not easy. Getting to their level (or thereabouts) requires years of practice, failure, experience, and, of course, skills and talent.

Likewise, the sample-based east coast style and sound has its entry point and master level. But the entry point for the sample-based east coast style and sound has a high entry threshold. Sure, anybody can get a sampler, a turntable, and a record or download an MP3 and start sampling. But, instantly making sample-based beats that are passable for much of what has already been accepted as decent requires a great deal more of skill and experienced. (Incidentally, this is one reason so many find it hard when they start out sampling; they thought it was easy before ever actually trying to do it.) Making sample-based beats in the vein of DJ Premier, RZA, J Dilla, or Kev Brown requires years of practice, experience, studying, lots of patience, knowledge-building, and, of course, skills and talent.

But what happens when the lines between the entry point and the master level, the top and the bottom, are blurred? More specifically, What happens when the entry point becomes just as acceptable — even competes with — the master level? When the entry point emerges as a lauded alternative to the master level, mediocrity takes on a whole new significance.

Odd Future: Much to Do About Something; Large Professor and Nas: Chasing the Standard of Their Time

Odd Future

Odd Future’s an interesting case. When they first came to my attention, I liked them. They showed promise. And while I didn’t consider them to be mediocre, I didn’t deem them to be great either. But I remember some years ago when Odd Future were media darlings, when journalists and bloggers alike blushed over how “fresh” and “creative” they thought Odd Future was. Some even made comparisons to Wu-Tang Clan. In the midst of the media hype surrounding Odd Future (which was driven in part by there supposedly must-see live-show antics), what was lost was that the beats (some dope by any standard) that they were using weren’t anywhere near as sharp or thought out as RZA’s, and the rhymes that they were reciting (some clever and thoughtful) were not quite on the same level of any Clan member.

In terms of beats in particular, Odd Future was praised by some as if they’d hit upon some futuristic style and sound that was going to revolutionize beatmaking. During Odd Future’s media-buzz heyday, I recall reading a number of write-ups that used one key word as the chief descriptor of their beats — “sparse.” Sparse was used so often by writers struggling to say something knowledgeable (or good) about Odd Future’s beats that it undoubtedly made some think that sparse was the new genius beatmaking method.

What few people cared to recognize or point out was that sparsely made beats (particularly those that feature little more than a kick drum, snare, hi-hat, and some odd synth sounds) were perhaps the best that the collective of teenagers could do at the time, not the intentional stripped-down genius of a Rick Rubin or Showbiz. Odd Future had something, but their something — not to be confused with spectacular — was recognized for being levels beyond what it actually was. As the story goes, they were young, just having some fun, and sharing their music for free on YouTube. But fun aside, clearly the collective took music seriously, even if they did at times act disinterested, as if the whole thing was one big shoulder shrug. And what makes Odd Future so interesting, in the scope of this article, is that they didn’t pursue mediocrity, yet when you look at their media buzz, it’s hard not to believe that the effects of mediocrity elsewhere didn’t help to shape how graciously Odd Future were received by the press. Still, what standard was Odd Future chasing?

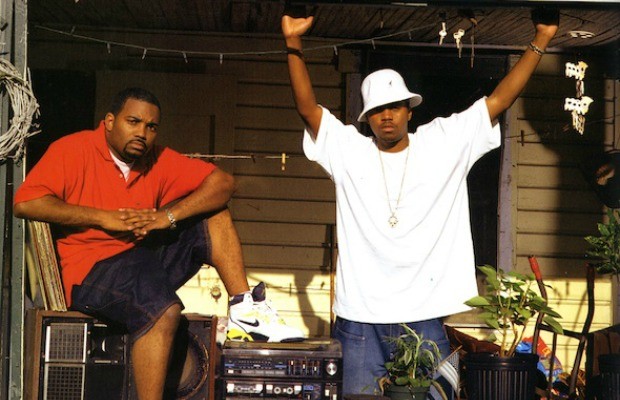

Large Professor and Nas

By comparison, consider a teenage Large Professor, who at 16 years old was a serious student of beamaking and at the beginnings of an iconic career. Or by further comparison, consider a teenage Nas (Nas was still a teenager when Illmatic came out!) connecting with fellow teenager Large Professor. In the case of Nas and Large Professor, look at the standard of their time: Marley Marl, Kool G Rap, Rakim, Paul C., DJ Premier, Pete Rock, Slick Rick, KRS One, Chuck D, just to name a batch of what was out when they took up the challenge of being hip hop/rap music makers. Mediocrity wasn’t acceptable when Large Professor and Nas began making hip hop/rap music. They couldn’t YouTube their way into popularity and then convert it into success. There wasn’t a music press eager to pore over their work with undue hyperbole. At the dawn of their careers, mediocrity wasn’t rewarded, it was avoided. During that time, this meant that all of the fun was in taking the art form seriously; which meant building skills up to the scrutiny of your peers; which meant being a vanguard at times. And all of this meant that the art form grew. This used to be the standard, the norm.

The Vanishing of Peer Scrutiny

But what if you don’t care about the scrutiny of your peers? Even worse still, what if peer scrutiny dissolves in favor of a generally accepted mediocrity? With no standards in place, taking the art form seriously or building up skills or becoming a vanguard is nothing more than a voluntary act. In this scenario, the market (mainstream or underground) isn’t demanding these things of an artist, as the widespread acceptance of (or indifference to) mediocrity shields the talentless and less serious music makers from any real (i.e. market punishable) scrutiny. If a 15 year old with no experience can make an entry-level trap song that competes with a master level trap song, tell me what incentive does that 15 year old have to further build his rhyme or beat skills? If the access to success and popularity are no longer buffered by skill or talent, knowledge or experience, then mediocrity inevitably becomes the norm.

Some would argue that this makes it better for the true artist to rise to the top. I beg to differ. The bi-product of a generally accepted underwhelming-ness is that the noise thickens and genuine enthusiasm, for anything, wanes. What’s considered to be good becomes whatever’s passing; while great becomes overshadowed by the weight of average, making anything not mediocre the “other.” And this can be dangerous, too, as the “other” can unduly be regarded as greatness. The truth is, mediocrity grants coverage; it shields people — do what everyone else is doing, and you don’t stand out. This way, no one knows if you’re good; more importantly, they also don’t know if you’re bad. Just reach for something that merely passes, make a YouTube video, and you have a shot. Hasn’t the formula proven successful time and again over the last decade?

Reward for Mediocrity and the Good News for Beatmaking

Reward for mediocrity means that hip hop/rap will never go back to its golden eras, where vanguard art growth was the norm. There are some who love to wax wise and say that it’s all a cycle, that it’s going to return to how it once was. Wrong. While there are some cycles in music that may repeat, there are others that die off when one era ends and another begins. And how it once was in hip hop/rap music is over. For good. No amount of wishful thinking or nostalgic zeal will ever displace the fact that the 90s, the 80s, or 70s are never coming back! Mediocrity has found a permanent home in the psyche of modern hip hop/rap music making, and the only thing left to hope for is that some future music makers avoid it. Still, mediocrity notwithstanding, art forms grow one way or the other…

The good news for beatmaking in all of this is that, overall, the beatmaking culture has always shunned mediocrity. There still is a rite of passage in the art of beatmaking: You don’t rise up until you’ve developed the skill and acquired the knowledge and experience; and you don’t get a name until your peers respect you. This doesn’t mean that mediocrity doesn’t find its way into beatmaking, it just means that no one who takes beatmaking seriously will ever accept mediocrity as a viable alternative. In this sub-culture of hip hop, the lines between mediocrity and excellence are never blurred (for instance: BeatTips Top 30 Beatmakers of All Time). Which is why beatmaking will always continue to lead the fight against mediocrity in hip hop/rap music.

—

The BeatTips Manual by Amir Said (Sa’id).

“The most trusted name in beatmaking.”

Odd future beats are wack. Interestly, roc marciano has mastered taking simple loops with minimal drums & made masterpieces. http://youtu.be/rzemawV9j9A